Confused by "balance" versus "scale"? Choosing the wrong tool can compromise your data. I'll explain the fundamental difference, ensuring you always make the right choice for precise measurements.

The fundamental difference is their principle. A balance measures mass by comparing an unknown mass to a known one. A scale measures weight by converting the force of gravity on an object into an electrical signal. This core distinction affects their precision, use, and calibration.

This difference in principle might seem small, but it leads to huge variations in precision1, application, and even how they react to their environment. I've spent nearly two decades in the weighing industry, and I've seen firsthand how crucial this distinction is. Let's break it down further so you can see why it matters for your specific needs.

Which device measures mass, and which one measures weight?

Are you measuring mass or weight? Using these terms interchangeably is a common mistake. This can cause significant errors in critical scientific or industrial processes. Let’s look at the clear distinction.

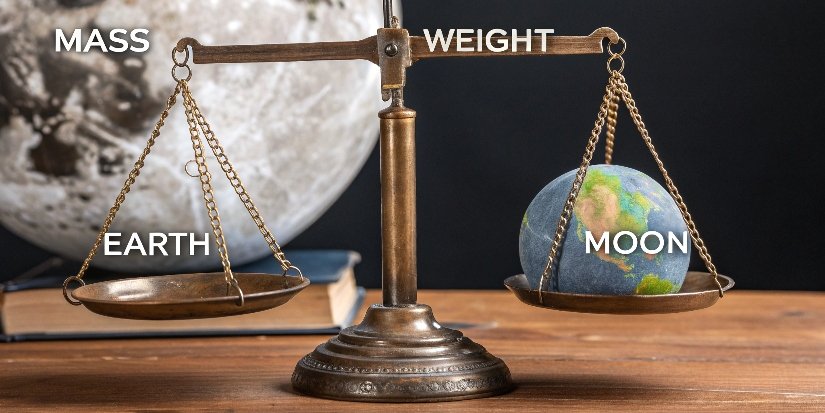

A true balance measures mass by comparing two objects, making its reading independent of local gravity. A scale measures weight, which is the force of gravity acting on an object's mass. This means a scale's reading can change depending on its location on Earth.

To really understand this, we need to go back to basic physics. Mass is the amount of "stuff" in an object, and it's constant everywhere. Weight is the force exerted on that mass by gravity2. Your mass is the same on Earth and the moon, but your weight is much less on the moon because of its weaker gravity.

Understanding the Physics

A traditional two-pan balance3 perfectly illustrates this. It works like a seesaw. You place your sample on one side and add known standard masses to the other until it's perfectly level. Because gravity pulls down on both sides equally, it gets canceled out. You are therefore measuring mass directly.

Modern electronic scales, like the industrial ones we manufacture at Weigherps, work differently. They use a sensor called a load cell4. When you place an object on the scale, it pushes down on the load cell, which converts that force—the weight—into an electrical signal. The scale's software then shows this as a weight reading. This is why a highly sensitive scale needs to be calibrated for its specific geographic location.

| Feature | Mass | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The amount of matter in an object | The force of gravity on an object's mass |

| Unit | Grams (g), Kilograms (kg) | Newtons (N), Pounds (lbs) |

| Constancy | Constant everywhere | Varies with location (gravity) |

| Measured By | Balance | Scale |

Why are laboratory balances considered more precise than digital scales?

Need hair-splitting precision but your digital scale isn't delivering? This inaccuracy can ruin sensitive formulas and expensive research. Here's why laboratory balances provide that next-level precision you require.

Laboratory balances are more precise due to their operating principle. Many use electromagnetic force compensation (EMFC), which finely controls a magnetic force to perfectly counter the sample's weight. This is far more sensitive than the strain gauge load cells in most digital scales.

The technology inside the device is what truly dictates its precision. As a manufacturer, I deal with these engineering trade-offs every day. For a heavy-duty industrial scale, you need something robust that can handle rough environments. For a lab, you need ultimate sensitivity.

Technology Dictates Precision

Most digital scales use a technology called a strain gauge5. It is a simple, durable, and cost-effective sensor. When a load is applied, a metal element inside bends slightly. This changes its electrical resistance, which the scale's processor measures and converts into a weight value. It's perfect for weighing boxes in a warehouse but doesn't have the finesse for sub-milligram measurements.

High-precision laboratory balances, on the other hand, typically use a mechanism called Electromagnetic Force Compensation (EMFC). Instead of just passively measuring force, an EMFC system actively generates an opposing electromagnetic force to lift the weighing pan back to its original position. The amount of electrical current needed to create this counter-force is directly proportional to the object's weight. This active, feedback-controlled system is incredibly sensitive and stable, allowing for readability down to 0.1mg or even 0.01mg.

| Technology | Principle | Common Use Case | Precision Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Gauge | Measures deformation under load | Industrial, Retail, Kitchen Scales | Good (e.g., 1g - 100g) |

| EMFC | Creates a counter-force | Analytical, Laboratory Balances | Exceptional (e.g., 0.1mg - 0.001mg) |

How does gravity affect readings on a scale versus a balance?

Worried your measurements won't be consistent across different locations? Variations in gravity can silently introduce errors, affecting quality control. Here’s how each device handles this invisible force.

Gravity directly affects scales because they measure force. A scale calibrated in one city will read slightly differently at a higher altitude. A traditional balance is unaffected because it compares two masses, and gravity acts equally on both, canceling itself out.

This isn't just a theoretical problem; it’s a practical challenge for any business that operates globally. Gravity is slightly stronger at sea level than on a mountaintop. It even varies slightly between the equator and the poles. For everyday weighing, this difference is negligible. But for high-precision science or tightly controlled industrial processes, it matters a lot.

Calibration is Key

As I mentioned, a classic balance is naturally immune to this because it’s a comparative tool. If you take a two-pan balance from sea level to a mountain, gravity's pull on both the sample and the standard weights decreases by the same amount, so the result stays the same.

A scale, however, will show a lower reading on the mountain because it's measuring the reduced gravitational force. This is precisely why calibration is so critical for scales. Modern electronic balances—which are technically very high-precision scales—often have an internal calibration feature. At the push of a button, an internal motor places a built-in, known mass onto the sensor. The device then self-adjusts its software to account for the local gravity, ensuring accuracy. For our international clients, we always stress that any high-precision scale must be calibrated on-site before its first use. It’s a mandatory step for reliable data.

| Device Type | How Gravity Affects It | How to Ensure Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Balance (traditional) | Effect is canceled out | No gravity-related adjustment needed |

| Scale (electronic) | Reading changes with gravity | Must be calibrated at the location of use |

In what practical situations should you use a balance instead of a scale?

Not sure whether your application calls for a balance or a scale? Choosing incorrectly wastes budget and compromises your work. Let’s look at practical scenarios to make it simple and clear.

Use a balance for tasks requiring high precision with small quantities, like pharmaceutical compounding, chemical analysis, or weighing jewelry. Use a scale for general purposes where speed and durability are key, such as in logistics, retail, or food portioning.

The final decision always comes down to the job you need to do. I’ve helped hundreds of clients choose the right tool, from massive truck scales to tiny analytical balances. A software company director once asked me if their team could use one of our industrial platform scales to do quality control on small electronic components. I had to explain that it would be like trying to measure a single grain of sand with a bathroom scale. The right tool for the right job is everything.

When to Choose a Balance

You need a balance when accuracy is non-negotiable and you are typically working with small amounts.

- Pharmaceuticals: Compounding medications where a tiny error could have major consequences.

- Laboratories: Chemical analysis, scientific experiments, and sample preparation.

- Jewelry: Weighing precious metals and gemstones where value is tied directly to mass.

- High-Tech Quality Control: Checking the coating on a tiny component or the mass of a new material.

When to Choose a Scale

You need a scale6 when you need a fast, durable, and cost-effective way to measure weight, often for larger items.

- Logistics & Shipping: Weighing packages and pallets to calculate shipping costs.

- Retail: Price-computing scales in grocery stores.

- Food Production: Portion control on an assembly line.

- General Industrial: Checking inventory, weighing scrap metal, or batching ingredients in large vats.

Conclusion

In short, balances measure mass with high precision for sensitive tasks, while scales measure weight for general-purpose use. Choosing correctly ensures accuracy and efficiency in your work.

-

Understanding the importance of precision can help you avoid costly errors in your work. ↩

-

Exploring the effects of gravity on measurements can help you understand the limitations of scales. ↩

-

Understanding the difference between a balance and a scale is crucial for accurate measurements in various applications. ↩

-

Understanding load cells can enhance your knowledge of how modern scales operate. ↩

-

Understanding strain gauges can provide insights into the technology behind many scales. ↩

-

Exploring how scales work can help you choose the right tool for your weighing needs. ↩

Comments (0)